Into the Obscuradrome 2/20/26

Welcome back to the Obscuradrome. I'm Bob Pastorella, co-host of the This Is Horror podcast, author of The Small Hours, co-author of They're Watching with Michael David Wilson, and Mojo Rising, which is out of print as of this writing. This is my newsletter, housed now at my website powered by Ghost.

The Hellish Jazz

That's what people called jazz in the 1920s. It was new and fresh and the kids loved it. It was all the rage and conservative people, especially in the south (racist white people) saw it influencing the youth and they. could. not. have. that ... no siree, that just wouldn't do. They demonized it, called it hellish and from the devil and of course that did nothing to stop it.

Probably made it more popular.

I came to jazz late. I played a trumpet when I was in junior high school because to get a guitar I had to learn music. I originally wanted to play sax, but trumpets were less expensive at the time and the school damn sure wasn't buying my instrument. And then I started learning music and actually playing the trumpet, getting into the ensemble band class in school. Our instructor was a jazz fanatic and made us listen to Miles Davis and told us that if we practiced and practiced then we might be as good as Miles one day. I knew that day was never going to come for me because I didn't want to play trumpet, it was simply a means to get the guitar, and there was no way I was going to be as good as Miles Davis because he was badass.

Skip forward ten years. I'm playing guitar in a band listening to Megadeth trying to explain to our drummer that Gar Samuelson, Megadeth's drummer at the time, was a jazz drummer, and Chris Poland, Mustaine's 2nd lead guitarist, also had a jazz background. I pled my case without even being a fan of jazz, but I knew enough about music to recognize what I was hearing, and dammit ... you can't tell me "Wake Up Dead" doesn't have a jazz beat. And our drummer shrugged his shoulders and said, "Fuck jazz."

He didn't last long.

Our next drummer was a percussionists, and trust me ... he got it. Dude's a teacher and still drums today.

This is all to say that today, with regret of not getting into jazz sooner, I'm still a beginner with the music. But I'm noticing some patterns, and making some connections. One of those connections is the undercurrent of gospel/esoteric/mystical/occult themes within jazz. That this particular genre of music (or perhaps ... mode?), with its almost complete lack of lyrical context, could even suggest such content is both fascinating and baffling.

Jazz originated in the south, specifically New Orleans, a city already shrouded in mystery and the occult. It's easy to see how gospel music infected jazz because gospel music was inherent in the culture there.

Jazz funeral, anyone?

In the beginning, while the church didn't want any part of jazz in their services, you couldn't keep jazz out of the church. It went along with gospel music intimately, which helped the infant music genre grow up and spread across the country. Yet, while gospel music has remained somewhat static is style (please correct me if this is an unfair generalization), jazz refused to be contained to one distinct style. The very nature of jazz emphasizes change, a refusal to stay in one place, or through one person. And though the gospel was unable to keep jazz in check, as it spread through the country, it took on an almost secular guise.

I say almost, because as time went on, more musicians found inspiration within their own religious values in jazz. John Coltrane was known to have been well read in the works of Madame Blavatsky, the Golden Dawn, and the like. A Love Supreme is a four part thirty-two minute prayer: "... by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music. I feel this has been granted through His grace. ALL PRAISE TO GOD” (liner notes from A Love Supreme). And need we not forget about Coltrane's 2nd wife, Alice Coltrane, who was introduced to meditation by her husband. After John Coltrane's death, Alice rediscovered herself, leaned on Hindu teachings for directional guidance, taught herself how to play harp, and then recorded classic jazz albums of her own like Journey in Satchidananda with Pharoah Sanders.

If the Coltranes represented the more peaceful side of faith within jazz, then it kind of make perfect sense that trumpeter Mile Davis aligned with the darker aspects, if not a lack thereof.

“Jazz is like blues with a shot of heroin!” —Miles Davis.

It wasn't so much that Miles was into the darker aspects of life, it was more than those things affected him when he was younger, and while he kicked most of those habits, heroin in particular, he was also well aware how the recovery from those ills would continue to affect him and his music. The one constant with Miles was change. He changed so much that he basically 'retired' from the scene because to him, that was a form of change. And each time he returned to jazz it was different. He had an almost supernatural sense of how music was going to change, the trends that would infect everything they touched, and he knew exactly how to tap into it.

Davis was called the Prince of Darkness because he was serious yet painfully reserved ... cool in more ways than just the sunglasses and sharp suits. Cool as in impenetrable, which made him a target for young journalists who would fall over themselves to only get sliced on the cutting block. Davis did not suffer fools. He did as he pleased and lived his life as he saw fit. Yet Davis was known to be superstitious, and believed in magick and the occult. During the 70s, his music took on a hedonistic approach as jazz fusion took over the genre. "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" is basically Miles getting ahead of the things stopping him. It seems he was a firm believer in "Do what thou wilt."

Sliding sideways just a little, at this point I'd be remiss to not mention Sun Ra, or John McLaughlin (who played on Davis' Bitches Brew) and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, or the aforementioned Wayne Shorter, or Chick Corea, or Herbie Hancock, all of which have given us spiritual contributions into the world of jazz.

The list goes on and on.

Jazz arose from the blues and gospel music, and continuously reinvents itself by spreading outward from those beginnings, embracing all forms of spirituality and mysticism much like it's kissing cousin, heavy metal. Even progressive rock is known for its spirituality and mysticism, so it's not so much a stretch to see how that came from jazz.

It's all in the music.

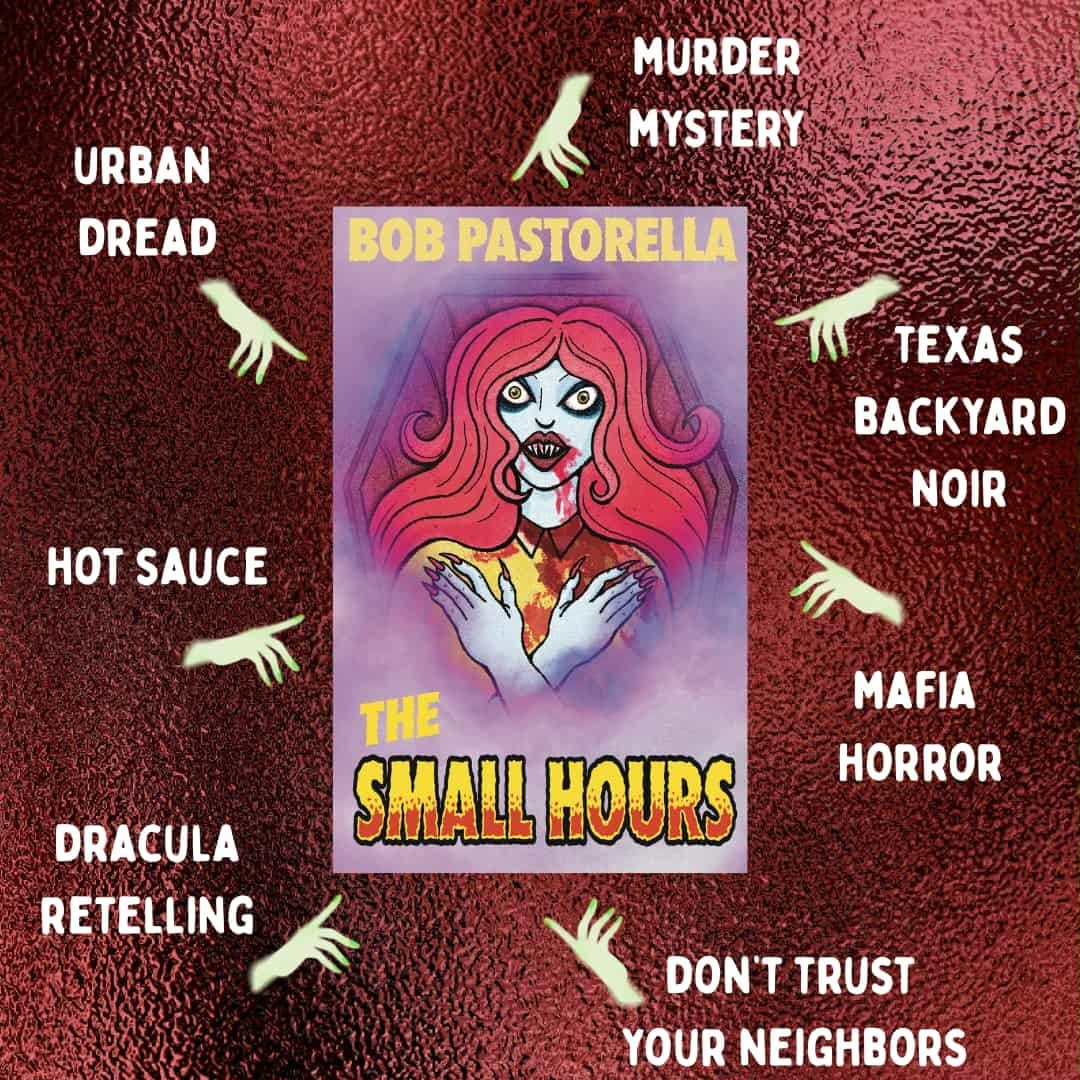

My splatterpunk vampire novel debut, The Small Hours is out now. Southeast Texas Backyard Noir meets small town Urban Dread. It's funny, it's horny, and it's so, so bloody. Think Fright Night meets Suicide Kings and you're on the right track. A playful and gory spin on a vampire classic.

Get it at the Ghoulish website

If you've read it, please leave a review.

I was on Matthew Jackson's kickass podcast The Scares that Shaped Us talking about the book and also about the seminal vampire film Let's Scare Jessica to Death. You can listen to that episode here.

I was also a guest on my own podcast, This Is Horror, when co-host Michael David Wilson flipped the script on my and put me in the guest chair. You can listen to that episode here.